CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOURNAL:

The recollections of a DUKW driver.

n.b. 'clicking' on some of the smaller photographs will enlarge them.

In 1956, one of the advantages of enlisting in the army (as opposed to waiting to be called-up for National Service) was an understanding there might be an element of choice in matters such as the regiment you joined, the trade in which you were trained, and where you were posted. In my own experience, this turned out to be the case in two of the aforementioned categories because I was allowed to choose the Royal Army Service Corps and I received a thorough training as a driver.

So far as my first posting was concerned, however, I don't recall being given a choice. Mind you, I did have a preference and, in that respect, I was fortunate because I had decided that, although I may have preferred to be posted to an extremely far-flung corner of the world (such as Singapore or Hong-Kong - as opposed to Europe), my second choice was to be as close to my home in the north-west of England as was possible, and the first posting I received, Chester, fitted the bill quite nicely.

For the most part, I can't deny that I was quite content during my time in Chester. However, as I had only signed on for three years, I realised it was unlikely that I would be posted anywhere else. So, after about a year, in response to an urge to broaden my horizons, I volunteered for a grueling ten-day course with The Parachute Regiment...........

Sadly, although I completed the course and actually got as far as making a descent from a tethered balloon, I wasn't awarded the coveted paratrooper's wings. Within days, however, my disappointment was put to one side because an earlier application to become a DUKW driver at the British nuclear tests in the south Pacific had been accepted and, early in 1958, I joined a dozen or so other drivers at a training course at an RASC Amphibious company in north Devon.

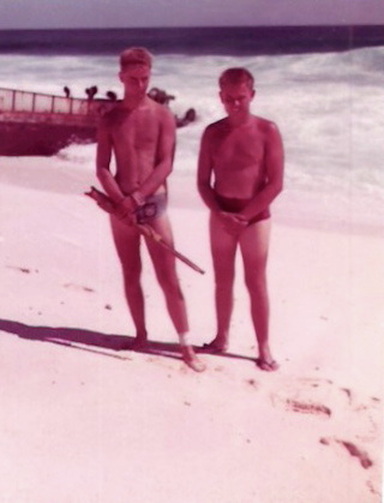

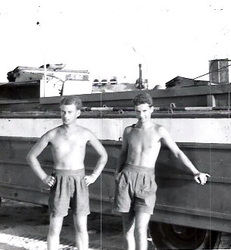

With the benefit of hindsight, I seem to have a more vivid recollection of off-duty moments than the military stuff. Visiting the cinema at the nearby town of Barnstaple, for example, or the pub almost opposite the camp gates - where I was introduced to scrumpy (cider) and a form of bar skittles which I hadn't seen before. I do, however, recall that the training was quite intense - in that we were required to learn an awful lot in what seemed like not very much time. It's so long ago (over sixty years, as I write) that some of the finer details may have escaped my memory; but, I can remember that we were billeted at a camp near the village of Fremington and that our amphibious training was undertaken in and around Instow, Appledore, Westward Ho, and Bideford Harbour - which is where we were introduced to larger landing craft such as the one behind the DUKW on the right (below). I'm on the left clutching a grease gun.

When we had completed our training, we all went to our individual homes for a period of embarkation leave; later re-assembling at the RASC Depot camp at Bordon in Hampshire where we spent a week receiving an assortment of injections and being kitted out with tropical uniforms and kit.

On the last weekend before our flight to The Pacific, Geordie Dixon, Barry Hands, and myself set out towards Aldershot for a final Saturday afternoon and evening in the UK. On the way, from the top of a double-decker bus, I caught sight of a small side-street garage which had a Ford Popular for hire (see below). Fortunately, Barry had a savings account; so, we jumped off the bus, found a Post Office, and persuaded him to withdraw sufficient funds to cover the cost of the hire - which (so far as I can recall) was about a fiver for the weekend.

Heading north, we realised it was too far to contemplate going as far as Geordie's home in the north-east; so I invited him to my home in the north-west. Barry lived near Birmingham and we dropped him off on the way. We returned to Depot Camp very late on Sunday night before I headed off to Heathrow airport on the following morning.

Although we hadn't known it until we arrived in Hampshire, the RASC unit at Port Camp on Christmas Island didn't just consist of DUKW drivers. There were also several bakers and a handful of tank-farm technicians - making a total of about three dozen - all of whom had assembled with us at Depot Camp before travelling to the Pacific. The first leg of the journey was going to be on civilian aircraft and we were scheduled to travel as far as Honolulu in small groups of three, four, five or six. This group (below), for example, who are waiting at a railway station en route to Heathrow Airport, consists of three DUKW drivers, two bakers and a tank-farm technician.......

javascript:;

We left the UK in March, 1958, and during the first leg of my own particular group's journey (from London to San Francisco), our QANTAS, Lockheed Super Constellation aircraft landed (presumably to refuel) in Ireland, Greenland or Iceland (I'm not sure which), Newfoundland and New York. I mentioned earlier that some memories of what happened are a little vague. Interestingly, however, although we were only there for two or three hours, I have vivid memories of La Guardia airport; and this is probably because we had quite a good view of the Manhattan skyline at night and, for the first time in my life, I saw a policeman with a gun at his hip. From New York, we flew over-night (crossing the lower reaches of The Rockies on the way) to San Francisco where we changed planes and boarded a United Airlines, Douglas DC7 for the flight to Hawaii.

As I mentioned earlier, we were sent out from the UK in small groups and I was fortunate enough to be in the first group - which meant that we were obliged to wait almost a week at Hickham US Air Force base whilst everyone else arrived. I was brave, though, and found little cause to complain. For example, the building on the left (below) is the PX (the US equivalent of the British Naafi) and, by British standards, it was unimaginably luxurious - as, indeed, was almost every aspect of the facilities enjoyed by American servicemen. Believe it or not, the buildings behind Sergeant Ted Lawrence (posing on the right) are actually the servicemen's billets; somewhat different to the corrugated-iron huts to which many of us had been accustomed in The UK.

In the fifties, the US Air Force owned one of the finest stretch of beach in Honolulu (above). In all probability, it will have been sold to property developers by now - but, in those days, service personnel had exclusive access to it and, since very few (if any) of those of us who had come out from the UK brought very much money, when we weren't posing in front of large American cars, we spent a lot of time kicking our heels along Waikiki beach within sight of the famous Diamond Head (see above).

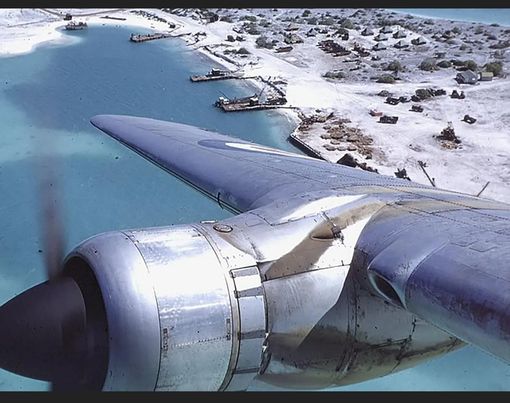

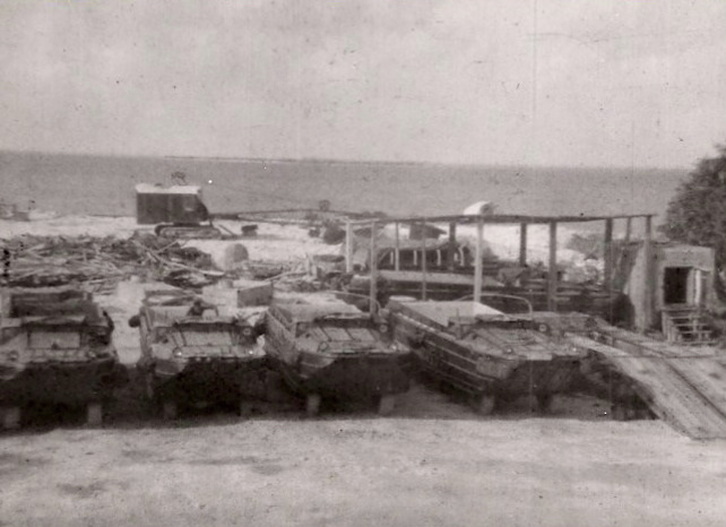

In time, the whole unit arrived at Honolulu and, although I had enjoyed the unexpected short break there (who wouldn't?), I wasn't too disappointed when we boarded an RAF Hastings aircraft (shown above) for the final leg of our journey to Christmas Island. The second photo (taken by a Denis Hobbs, RAF) shows the wharf area of Port Camp, and in particular (to a keen eye) a line of DUKWs in the area which became known as the DUKW Park. The photos shown below illustrates why we went there.....

<< CHRISTMAS ISLAND:

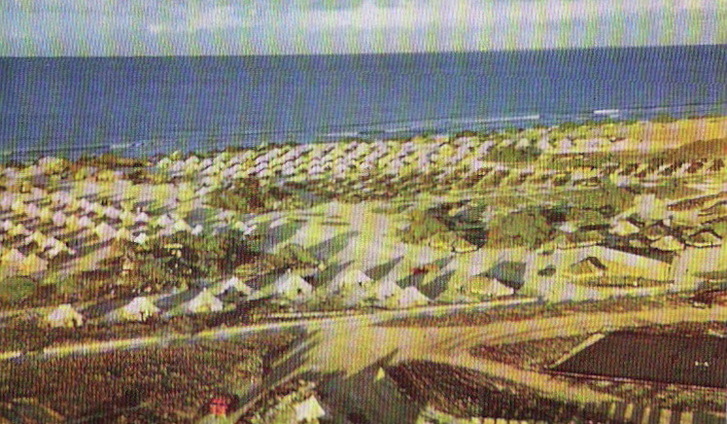

Port Camp (in recent times called Port London and shown in more detail in this adjustable map) is located in the top left-hand part of this photo and quite a long way from the airfield which is near the top right-hand corner of the island.

n.b. Some of the tests were conducted over the area at the bottom right-hand corner of of the picture.

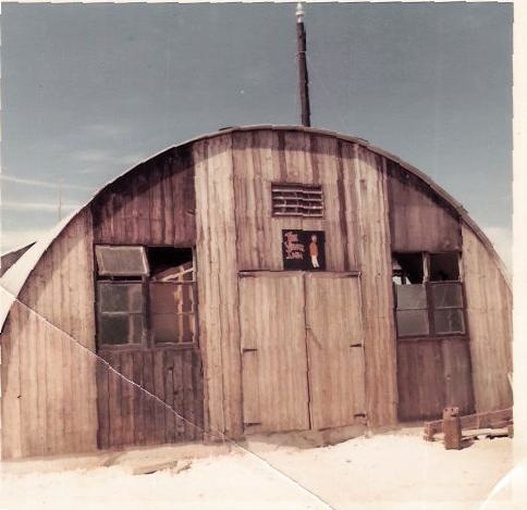

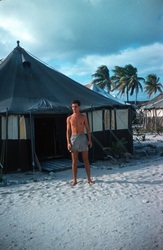

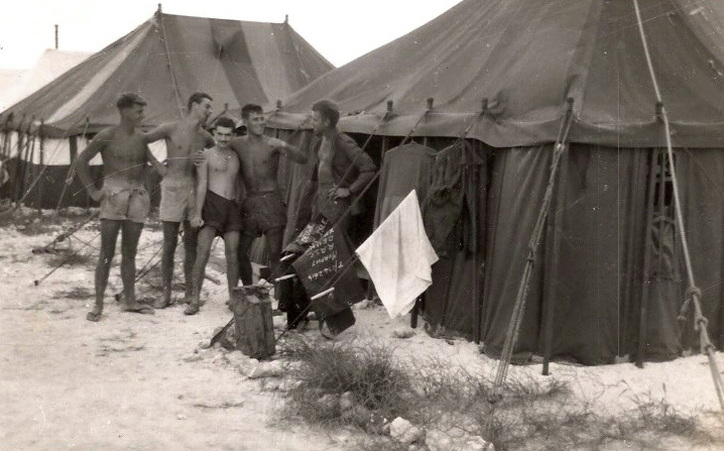

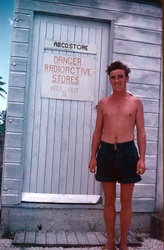

After landing on the island, we were driven by truck along unmade roads (above) to Port Camp. On the way - about half-way between the airfield and port Camp - we passed Main Camp where the vast majority of servicemen on the island were based. Soon after we arrived, it became obvious that the number of new arrivals was greater that those we were replacing. So, myself and some of those with whom I was about to share a tent for the next year, had to erect it ourselves (below). Note how white we were. Pale-skinned, newcomers to the island were known as ''Moon-men" and that's what we were, at that time. The planks lying on the ground behind us were what was left over after we had constructed a raised floor and, in an uncharacteristic display of craftsmanship, I used some to make a bedside cabinet (below).

We inherited a couple of interesting 'gifts' (above) from the RASC personnel we were replacing. The fact that our tent was quite close to the cook-house meant that the rather quaint Donald Duck-inspired sign would have been familiar to almost everyone in Port Camp. Why the kitten - who seems to be trying to savage my boot - should choose to move to a newly-erected tent is something of a mystery. Perhaps, the proximity of the aforementioned cookhouse (behind me in background) might have been a factor. Mind you, since Port Camp was really a Royal Navy base, it was actually called a Galley. Here's another picture of it (below). The contraption in the foreground is where we washed our eating irons and trays.

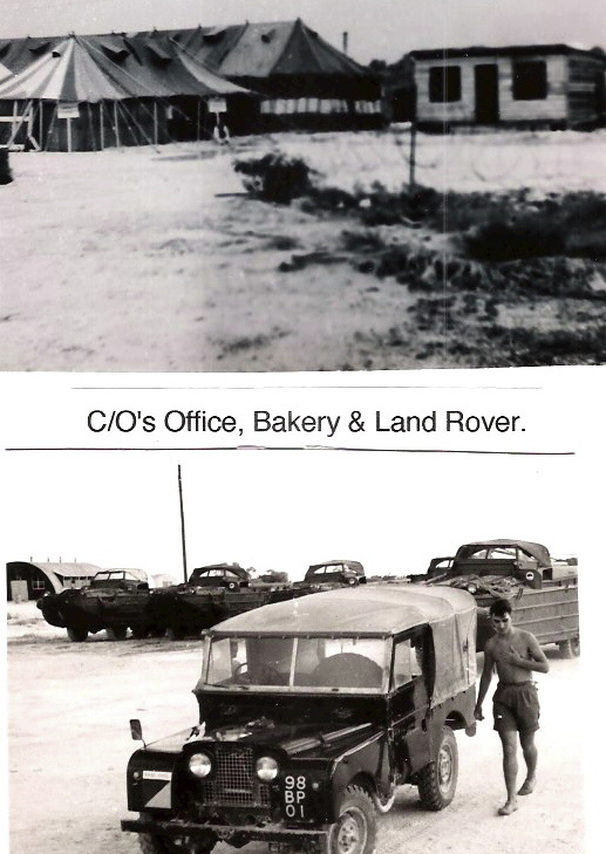

The correct address for the military base where we were stationed on the island was HMS Resolution, Christmas Island, BFPO 170, and army or RAF personnel stationed at Port Camp were actually 'on detachment' to The Royal Navy. However, each unit retained it's own identity and, to distinguish us from the rest, the RASC flag was flown above the CO's office (below). Although we assembled in front of it, each morning, I don't recall attending what might be called a 'parade'.

Parades - or, indeed, any other military routines which we might have been used to in the UK, weren't something which featured very much in the working days of DUKW drivers during the build-up to a series of nuclear tests. On the contrary, from a personal point of view, what we were involved with in the south Pacific was the nearest I ever got to 'proper' work during my time in the army. Instead of training - i.e. pretending - what we were doing was the real thing and we were at what is now considered to be the front-line of the 'cold' war.

Very little on the island came about without an element of imagination and initiative coming into the equation. The tent which had originally been used as the RASC headquarters (shown earlier), for example, was replaced by a wooden structure which had been cobbled together using packaging materials which were surplus to requirement when the crane (above rear) was assembled. The vehicle-ramp (front-right above) had been two low-loaders which were abandoned by US forces following WW2. After commandeering the crane to lift one half onto some wooden blocks, I managed to get someone to cut out a working area down the middle of it. Similarly, a former walk-in refrigeration unit (behind the ramp) was converted into a store-room. Using surplus planks again, I manage to cobble together the steps at the entrance. Interestingly, at the time the photograph was taken, we were in the process of constructing a shaded area (to the left of the store-room) where Ted and his happy helpers could get some respite from the sun whilst working on a DUKW. Pillars had already been driven into the ground and a roll of tarpaulin on top of the construction was waiting to be unfurled.

Incidentally, equipment which had been abandoned during the years of USA and the UK military 'occupation' of the island developed into something approaching an ecological disaster in later years.

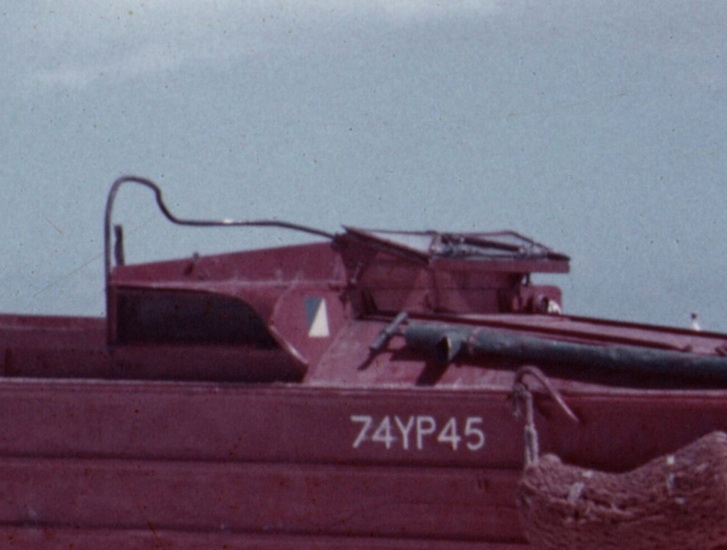

Because we were so busy and what we were doing was so crucial, one of the most important roles in our unit was to keep the DUKWs in good condition - and that responsibility was taken on by Sergeant Ted Lawrence (above centre). Almost single-handedly, he maintained and serviced all of them. Keeping a fleet of DUKWs running in sub-tropical conditions is a bit like painting the Forth Bridge. Indeed, painting them (in red-lead) was as crucial for their overall well-being as was the mechanical stuff. So, although he was assisted by others, generally speaking, the entire DUKW operation was single-handedly held together by Ted.

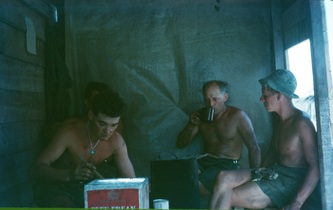

Working in the DUKW Park - as it was known - was thirsty work and, each morning, someone was delegated to commandeer an old tin can from the bakery (which was next to the HQ), fill it with water, place it on top of some discarded timber or loose branches, soak it with fuel (the wood - not the tin can) and throw a match towards it; and, later, carry it back to a lean-to we had constructed as a 'Rest Room' alongside the HQ. On the left (above) are Alan Gott and Freddie Frith and Alan appears again with Ted Lawrence and Ray Chimes.

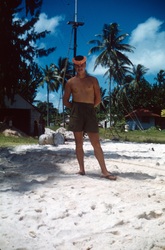

Shown below are some of our unit in and around the DUKW Park. Our every-day mode of dress consisted quite simply of a pair of shorts, a hat or beret, and army-issue plimsoles or Royal Navy-issue sandals and after a few weeks, we ceased to be 'Moon-men' and had developed quite substantial suntans. In fact, in my own experience, despite liberal applications of sun-tan lotion (obtained from the Naafi) the skin on my nose peeled away several times during our stay in the south Pacific.

Who's who (below)

(left) L to R: Ted lawrence, Ray Chimes, Dave Durrant, Barry Hands.

(centre) L to R: Alan Gott, Freddie Frith.

(right) L to R: Geordie Dixon, Freddie Frith, Dave Durrant.

Apart from maintaining the DUKWs, our main function on the island was to bring ashore perishable goods from the RFA supply ships (right below) which were anchored about a mile-and-a-half from Port Camp. Most ordinary provisions were brought ashore on LCMs (Landing Craft Men) which were operated by Royal Marines. The disadvantage of this method, however, was that, double-handling was involved. This meant that goods were lowered from the ship onto the LCM (left below) and then transferred onto trucks for further transportation to the stores once the LCMs reached the port.

With DUKWs, however, double-handling wasn't necessary and it took significantly less time to take perishable goods (frozen food, mainly) directly to the stores. Our excursions to and from the supply ships involved sailing fairly close to some razor-sharp coral reefs and I can recall from personal experience that breaking-down under those circumstances can be a bit scary. So, for reasons of safety, our DUKWs always carried a crew of at least two and travelled in pairs - or more.

Except in very unusual circumstances, the DUKWs would always pull alongside the supply ships whilst travelling against the prevailing current. Then, having secured ourselves to the side of the vessel, the provisions were lowered down to us.

In this series of photographs, the cargo is frozen meat and, as was more often than not the case, no matter how many DUKWs might be involved - the one furthest away from the supply ship would be loaded first. In instances when there were four DUKWs, the two outer ones could set off for the shore when they they were full and, if my memory serves me right, that had been the case on this occasion. However, it seems likely that (in the photo below) the two DUKWs nearest the supply ship were already partly-loaded when the other two arrived - and it's only as I write (more than sixty years later) that I realise we've lined up in numerical order.

Once a DUKW was fully-loaded, tarpaulin covers were used to protect the food from the intense heat - a factor which accounted for the fact that many of us became quite adept at steering with our feet (as shown below). It wasn't uncommon for the temperature to reach 120 degrees and the heat in the footwell of the vehicle could become almost unbearable.

Quite often, during our journeys to and from the port, we were accompanied by schools of dolphins. They seemed to be playing games with us - slowing down and accelerating in unison with us. They particularly liked to keep just in front of - or even under - our bows - as demonstrated by these photos which I took whilst standing on the DUKW engine cover). At the time we had thought they were porpoises but this suggests otherwise.

The advantage DUKWs had over LCMs is illustrated rather well by this photograph (above). The goods from the two LCMs in the centre of the wharf are being unloaded, by crane, onto lorries - whilst, at the same time, the DUKW on the right drives straight ashore. Enlarging that part of the photo (below) not only illustrates that we were carrying a fairly substantial load - but also reveals the somewhat nonchalant attitude of two of the crew perched on the top of the crate.......

The buildings to left of the LCMs and crane in the higher picture are part of the Royal Navy and Royal Marine's complex. One of them (shown below) was operated by the Naafi and was very popular with merchant seamen from the RFA supply ships - and the crews of the occasional Royal Navy vessel which might be visiting the island. It had an interesting name (see caption below photo).

Having mentioned visiting naval vessels, another task DUKWs undertook was to carry oxygen cylinders out to some of them who patrolled the south Pacific area for weather tracking and security purposes prior to and whilst the nuclear tests were being carried out. In the photo (above, right), a DUKW is alongside the warship which, in turn, is alongside a supply vessel. I have a feeling this particular vessel may have been called KUPAKI (or similar) from the Royal New Zealand Navy.

Each DUKW had a crew of two - usually comprising a lance-corporal (rather grandly known as the coxswain) and a co-driver. So far as I can remember, the pairings were decided during the training course in north Devon and my co-driver was Alan Gott. Paradoxically, I can't find a photo of us together; so, for the record, Alan - a proud Yorkshireman - is on the extreme left (above) standing next to another Yorkie, Freddie Firth. To complete a trio of Tykes, the driver in the middle's nick-name was Pudding. He's holding a coconut - something some of us used to paint, write a name and address, attach postage stamps and send them home to friends and relatives. I'm standing next to Geordie Dixon (far right) who was part of the 'hire-car' episode on our last weekend in the UK.

Although we didn't wear very much on the island, what we wore for work used to get really dirty and, since there were no laundry facilities at Port Camp, some of the indigenous Gilbert & Ellis islanders - who were employed as stevedores on the wharf - used to offer to take our washing in return for soap, soap-powder, and (I'm almost certain) cigarettes.

The stevedore who took Alan's and my washing was called Noaki - shown below (on the left) and a friend with the local village in the background - a really pretty sight. Unfortunately, however, their latrines were located at the end of jetties which extended into and over the lagoon and, as a consequence, when the wind blew in a particular direction, the smell wasn't very nice. Noaki and his wife, Elizabeth (who actually did the washing) are shown with their little girl In the other photo.

Alan and I were privileged to be invited by Noaki and Elizabeth to visit their village - which, under normal circumstances, was strictly out-of-bounds to service personnel. (The lure of young females could be a potent magnet for sex-starved young men and there were rumours of a drunken squaddie meeting his maker at the end of a sharp blade after breaking into the village one night). On a happier note, as soon as a camera appeared, a group was formed. This was especially interesting because (unlike more modern times) there was no attempt to seek monetary gain; they just seemed to like having their photograph taken.

Not everyone, however, liked having their photograph taken - or, in some case, even knew it was being taken - as illustrated by this photo of me heading towards the shower shed (below). To compound the deviousness of those responsible (and they know who they are), they even went so far as to send a copy of it to my fiancee - who later become my wife.

Routine was important in an environment such as we experienced on the island. Having a shower after work was an example. Another thing almost all of us did every day was to return to the wharf for a late-afternoon swim before the evening meal. Probably because I was afraid of getting my camera wet, I don't have any photos of this ritual ; however, a glance at the earlier picture of the DUKW coming ashore will reveal where we used swim. A highlight of the occasion was diving off the jetty or - for the more adventurous - the top of an LCM.

After the evening meal, there was usually something or another going on to help pass the time away. Apart from a new film being shown almost every night at the luxurious cinema (above left) the opportunity to buy a can or two - or more - of beer was on offer at the Naafi (top-left behind the cinema screen). Organised and semi-organised events included inter-unit rifle shooting competitions or football matches on the pristine playing surface to the right of where Barry Hands is spending a penny (above right). Another popular pastime was night-time tuna fishing in the lagoon behind the Naafi. A couple of us - Barry Hands (below - extreme right front row) and me behind him - occasionally borrowed the RASC Land Rover to attend Rover Scout troop meetings at Main Camp.

On the island as a whole, there were probably more airmen than seamen and soldiers and, although there were few (if any) of them based at Port Camp, the RAF's presence was felt almost every day in the form of "Flight Lieutenant Flit" - as we called him. This was the light aircraft (left above) who carried out frequent sorties spraying disinfectant over the island. Another frequent flier was the bright yellow air- sea rescue helicopter (right).

Interestingly, the RASC - and 'our' tent in particular - had a connection with the RAF because the tank farm where the fuel which was piped ashore from the RFA oil-tankers was operated by three RASC personnel (above) together with their sergeant. From there, the fuel was taken in bowsers to Main Camp and the airfield.

Although the bowsers were supposed to be driven by RAF drivers, one day Spud Murphy decided to take to the wheel of one and, in doing so managed to knock over a palm tree. As a consequence of this innocent misdemeanor, he was invited to spend a few days at 'Her Majesty's Pleasure' in a secure lock-up facility at Main camp and I was detailed to act as his escort. So far as I can recall, it was the one and only time I was technically properly dressed during my time an the island (below left). Normally, like everyone else. I was more casually attired (right).........

Having mentioned earlier how most of us had become nicely tanned, the bakers in our RASC unit stood out from the crowd because, working inside the field-bakery all day, they were comparatively pale compared to the rest of us. Baker Bernie Wynne from Manchester (below) is an example of what I mean.

Being a DUKW driver during the nuclear test series was undoubtedly one of the most interesting 'jobs' it was possible to have on Christmas Island; not least because, unlike almost everyone else who was posted there, we didn't stay on the island all the time. The reason for this was that many of the neighbouring islands which were used for weather-tracking purposes were inaccessible to ordinary vessels because they were surrounded by razor-sharp coral reefs. In a DUKW, however, the pressure in each individual tyre can be regulated with controls in the driver's compartment. So, it was possible to alter the tyre pressure to suit conditions for any particular beach and even deflate the tyres completely before driving over coral. The tyres were then re-inflated afterwards.

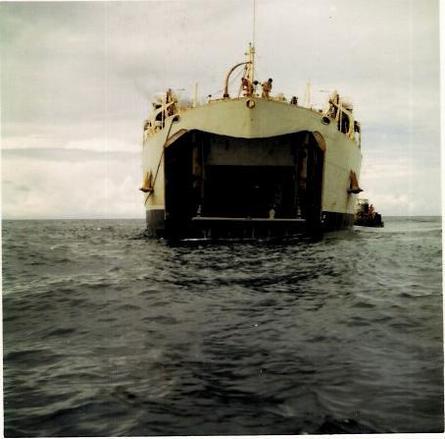

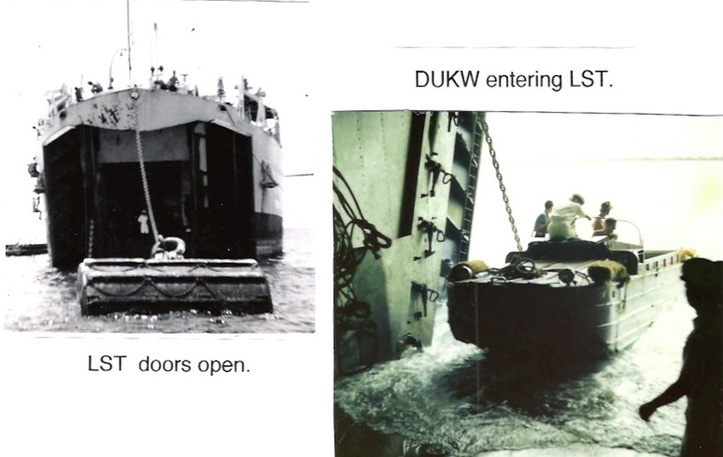

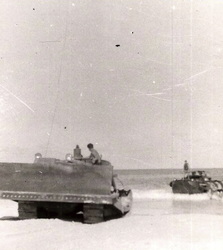

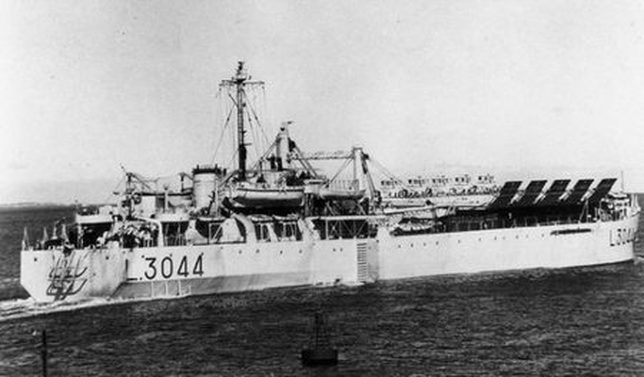

During these trips, we would always sail on board HMS Narvik (see below) a Royal Navy LST (landing ship tank) and it was at these times that we began to understand the significance of the training we received in Bideford harbour. In particular, the importance of timing the 'run' when driving towards the bow doors and into the cargo hold........

The top picture of the Narvik illustrates how the ocean's swell can cause the ramp between the bow doors to rise out of the water. So, not only does the driver have to negotiate a passage around the buoy in front of the ship (above and below left) but he has to ensure that he arrives at the precise moment that the bows are travelling in a downward direction (above right). The alternative of being trapped underneath the ramp doesn't bear thinking about.

There is only room for two DUKWs in the Narvik's hold; so, any additional DUKWs have to be hoisted onto the deck (above right) and secured to the deck by ropes - some of which can be seen attached to the rear of the DUKW (below).

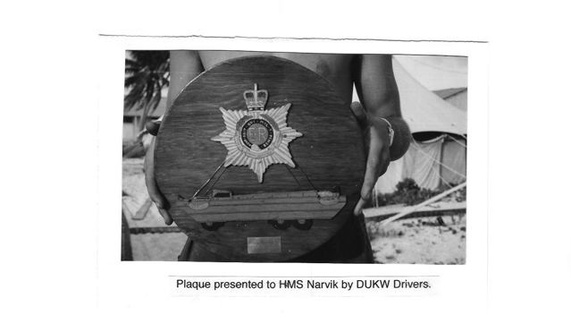

This plaque (shown below) was presented to the crew of the Narvik when the nuclear tests were finished and she sailed off to oceans new. I'm rather proud of it because I'm not known as a 'handyman' type of person. My design was intended to illustrate a DUKW being lifted in the manner of the top right-hand picture (above).

During some of these trips, members of the other RASC units came along 'for the ride'. I know some of our friends from the tank farm came with us, occasionally, and on the evidence of the photo on the left (below) a baker joined us. In the other photo, three DUKW drivers are joined by a Narvik crew member. Like many seamen he was known by his nickname and, although I'm usually quite bad at remembering names, I believe his was Bugsy or, perhaps, Bagsy. In either event, he was an OK bloke. By the way, make a mental note of the shape of the rail behind the driver (below left).

As I mentioned earlier, tyre pressures on DUKWs can be adjusted and, during our time in the south Pacific, nowhere was that feature more appreciated than at the island of Malden. Sailing there, by the way, presented those of us who hadn't done it before with what would be a significant moment during our time with the Royal Navy; because, to get there from Christmas Island, the equator had to be crossed. Sadly, I don't have a photo - nor, indeed, an accurate recollection of the occasion (drinking rum was involved). However, a "Crossing the Line" ceremony is considered to be an important 'rite-of-passage' in a naval career.

Like many islands in the region, the only fairly safe way of reaching the island was by DUKW. On a previous visit, the Royal Marines had tried to take equipment and provisions ashore on an LCM with unfortunate consequences - the wreckage of which can be seen behind Jim Thompson and myself (below). Incidentally, the disaster happened during the time the unit we replaced were 'on duty' and, although I don't know the precise details, I do know that DUKWs were involved in a rescue attempt and members of the RASC were awarded medals for their bravery.

The problem, by the way, was that the only stretch of beach which could be reached was through a particularly narrow gap in the reef. To compound the problem that particular stretch had been pounded by the the ocean to such an extent that, at the point where the sand met the sea, there was a steep drop of several fathoms - a wall, in effect. As a consequence, extra-special care had to be taken when attempting to get ashore. So, the beaching operation was controlled from the shore - in this case (below) by our CO.

The fact that we all wore life-jackets (see below) provides a clue to how tricky the procedure could be. In much the same way that assessing the swell of the ocean was critical when attempting to drive through the bow doors of the Narvik, as might be the case with a surfer, it was important to approach the shore at the same time as a wave was arriving. Not surprisingly, some drivers were more successful than others; but, more often than not the driver would only get the front wheels of the DUKW as far as the sand. At that point, whilst he struggled to keep at a right-angle to the shore, his co-driver handed a metal rope (which was attached to the front of the DUKW) to a gang of RAF chappies who had another rope (which was attached to a bulldozer) and, when the two were connected, the DUKW was pulled ashore.

Sometimes, we would carry very heavy stuff ashore (top photos above). Getting it into the DUKW was quite easy because a crane will have lowered it down from the Narvik. Getting it out of the DUKW, however, was a different kettle of fish because there was no mechanical lifting equipment on Malden. So, if something was too heavy to be lifted manually, a device called an A frame was erected on the rear deck of another DUKW. At the top of the A frame there was a pulley wheel over which the cable from the DUKW's winch (also situated in the rear deck) was looped; forming what, in effect, was a crane (see below).

Occasionally, it was necessary to dig a trench for the DUKW with the load to drive into whilst the other DUKW was positioned to enable the lifting operation to commence (above). If there was an exceptionally heavy load, two A frames were used (below). Once the load was raised, the now-empty DUKW drove away and the load was lowered to the ground.

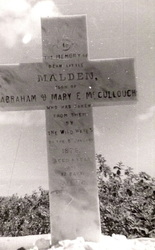

Malden was an especially barren island. There is evidence of it being inhabited in Victorian times and it must have been an awfully desolate place to live - and die. The grave shown below is dated 1876 (click to enlarge). It's for a child named Malden - after whom it might be supposed the island was named. Earlier nuclear tests had been carried-out there - which might account for the fact that, so far as I could tell there wasn't a single tree on it and, apart from the Naafi, the only form of 'entertainment' available to the troops was the opportunity to swim in a lagoon (below right). I heard recently that it had been created by the RAF with a few sticks of dynamite. Whether this had been a considered decision or the result of spending too much time in the Naafi is a matter for speculation.

At some time or another (I can't recall if it was before, during, or after the tests), we were visited by a group of extremely top, top brass. He won't be impressed that I'm not absolutely certain if he was amongst them - but I believe the Duke of Edinburgh may have been in the party. I do know he visited the island.

We spent a lot of time and energy bulling up a couple of DUKWs for the visit. Careful examination of the photo below will reveal that the left-hand one had a plate on the bow showing at least two stars and the right-hand one may have had as many as four. Another concession to their importance was that some steps appeared from somewhere. Ordinary DUKW drivers weren't afforded that luxury.

One of the other island we used to visit was called Fanning. Unlike Malden, although primitive by western standards, it was inhabited by a vibrant community and, although we had visited quite a few times, one particular visit was notable because it had been decided that some civil-engineering work would be carried out by The Royal Engineers.

Seeing DUKWs being hoisted onto the Narvik had been impressive on previous voyages - but, watching the amount of equipment being taken aboard on this occasion was awesome. Hardly an inch of space was wasted. Even our DUKWs were fully loaded as demonstrated by the one on which Ted Lawrence is standing (below right).

In addition to our usual quota of DUKWs, there was a significant amount of road-building equipment - together with what seemed like a small flotilla of LCMs to take them ashore when we got there. As we sailed away from Christmas Island, I recall thinking I had never seen the Narvik so low in the water (below).

Visiting Fanning (above and below) was always a pleasure. So long as the DUKW was steered through the gap in the reef, where we used to beach was quite accessible. Furthermore - whereas (for obvious and necessary reasons) the villagers at Christmas Island needed to maintain some distance between themselves and the troops - on Fanning the natural welcoming nature of the Polynesian people flourished and the urge to form a group whenever a camera came into view was as strong as ever.

On the island istself, because the DUKWs had the A frame system we had used on Malden Island, we were quite often used as mobile-cranes. Here, for example (below), a fairly large crate is being 'delivered' to somewhere on the island. Evidence of corrugated metal buildings (behind the DUKW below) suggests that this part of the island was occupied by The Cable & Wireless weather station company who had a base there.

In our experience, Fanning was the nearest thing we encountered to a 'desert' island - as depicted by Hollywood. Furthermore, in those days, it hadn't been corrupted by influences from the 'modern' world. The villagers really did live in huts made of reeds (see above), for example, and young girls wandered about bare-breasted - as demonstrated during the occasion I took a party of children for a trip out to sea (below). Fortunately, they were probably as fascinated by this strange young white man who drove in and out of the sea as I was by them.

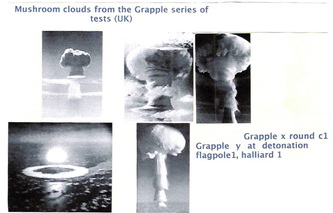

Back on Christmas Island - certainly for the first half of the year we spent there - our life remained pretty hectic as, during those our first six months, five nuclear devices were tested over or very close to the island. There are several publications explaining the procedures involved and, other than admitting that the realisation that I could see the outline of my bones as I pressed my hands into my eye-sockets during the explosions will probably go down as my most lasting memory, I don't intend to dwell on them any further. Here, however, is a video of the occasion and (below) one of the pretty pictures which our masters gave as as a memento......

On a 'test' day, after the 'all-clear'had been announced, most people would spend the rest of the day relaxing or taking part in recreational activities which were meant to take our attention away from the cloud hovering ominously over the far end of the island. Many of these diversionary exercises took place on water. LCM racing or sailing dinghies, for example (below).

All these 'leisure' activities were OK for most. From the DUKW drivers' points of view, however, it was a form of work because we were commandeered to ferry participants and spectators. One DUKW (below) was even used to carry a calypso band around the 'regatta'.

Later, during the second half of our stay on the island - and at a time when the period of frantic activity prior to and including the nuclear testing had eased off - DUKW drivers were, once again, commandeered for the purpose of providing 'leisure' - mainly for others. Each weekend, some of us would ferry troops across the channel which separates the lagoon from the Pacific Ocean to Cook Island. This was where Captain Cook had come ashore on Christmas Eve, 1777. At the time we were there, it was known as a bird sanctuary.

Bird-watching's OK, however, from our point of view - and DUKW drivers did secretly enjoy going there - Cook Island was a wonderful place for swimming, snorkellling and, in particular - where we could get a close-up view of the coral. By the way, I'm acting as bookends for Barry Hands in the following sequence of photos and, not for the first time, he 'stole' my camera. Since the only birds around were of the feathered variety, few of us bothered to wear swimming trunks.

Here we are (below) arriving back at the wharf after a trip to Cook Island. Whilst looking at it, I can see that if affords an opportunity to get a better idea of where we used to go for our swim each evening - which is just behind the LCMs on the right.

Some time around the middle of our stay, I sustained cartilage damage to my left leg. A pallet of provisions was being lowered and, for reasons which were never established - it could have been a malfunction with the supply ship's lowering device or an unexpected swell causing the DUKW to rise unexpectedly - but, for whatever reason, my knee was trapped between the pallet and the rail behind the driver's seat. Evidence of the incident can be seen in the picture of the rail (below). Prior to the impact, the rail looped upwards - forming a shape a bit like the roof of a car (as demonstrated in an earlier photograph I invited the reader to remember).

Anyway, by an interesting coincidence, at about the same time all this occurred, the person who had carried out the clerical duties for the unit returned to the UK and, since I could spell a little better than most, I was marched (or, should I say, hobbled) into the CO's office and, although I still got to enjoy my fair share of trips to neighbouuring islands, for the rest of my time there, I became a jack of all trades.

In addition to office work (I learned the basic principles of typing, for example), I became the unit's painter - being responsible for all the insignias and lettering on the DUKWs. I also played a big part in carrying out the aforementioned scavenging work which led to the various improvements to the DUKW Park mentioned towards the start of this account.

From what I've recounted up to now, it might be easy to assume that it was 'all-go' for the DUKW drivers. In fact, being busy was a blessing in disguise because we had very little time to become depressed (like many did) and the fact that we were able to visit other islands gave us an advantage over most other servicemen. Apart from one or two of our unit who visited New Zealand with HMS Narvik, for the rest of us, an opportunity to vacation (as the say in the USA) in Honolulu was irresistable (see above).

Those from our unit who went on leave, travelled in twos or threes and, for my part, I was joined by Jim Thompson from the tank arm. We stayed at the US Air Force's 'holiday' camp which was much nearer to the town center than Hickham base and, as I mentioned earlier, enjoyed a prime position on Waikkii beach.

On our second day there, I managed to find a small, friendly, garage who were prepared to let me invest in a hire-car for a couple of days. Although I wouldn't be surprised if someone else might have done the same, I didn't hear of anyone who did. In any event, once I had overcome a slight hiccup (driving on the wrong side of the road in the USAF base) Jim and I enjoyed a leisurely tour around the whole island.

Sometime after Jim and I returned from our leave, our CO, Captain Charles-Jones, was replaced by another RASC Captain. I guess the plan was for the new CO to 'learn the ropes' before our replacements arrived and I suppose in many respects, he did. However, one of the reasons I haven't named him is that it did seem to me that he let himself down rather badly when he allowed a rather cheeky Royal Navy storeman called Mac (above left) to supply us with blue paint instead of the usual red-lead.

Can you believe it - BLUE ??!! We became the laughing stock of Port Camp. From the shore, our DUKWs were practically invisible when at sea and the upshot of the sorry affair was that we had to paint a white line around the upper part of our DUKWs (above right) - which ended up looking like Birkenhead Corporation buses.

During our last two or three months on the island, evidence of attempts to modernise the place began to emerge (above). A tarmacadamed road to Main Camp and beyond was laid down, for example - and, not far from our tent, new buildings were being constructed. Up to then, so far as I was aware, the only substantial building on the island was the church at Main Camp (above).

n.b. I've recently come across this interesting web-site showing the island as it now is. A look at Google Earth, however, suggests that the photographs shown have been selected to appeal to tourists because most of Port London has been significanly modernised since our time there.

Not long before our unit was due to leave the island, I was one of three who had applied for and been allocated a very small number of seats which were available on a Hastings aircraft carrying RAF officers undertaking a twice-yearly inspection of their bases around the world.

The rest of our unit - who returned along more or less the same route we had taken coming out, left almost three weeks before us. So, those of us who stayed behind had what amounted to a 'holiday' - during which time we played a bit of tennis on the recently-constructed courts, some swimming, and some leisurely sailing.

One evening in March, 1959, however, tank farm technicians, Spud Murphy, John Treherne, and I took our final look across the lagoon (above) before spending our last night on the island prior to the first leg of our exiting journey home.

Out first stop was in Fiji and, as since there wasn't an RAF base there, we stayed in an hotel. Even though, in those days, facilities in Fiji were quite basic, imagine how luxurious sleeping in a room seemed after a year under canvas. The following day we flew to an RAAF base in Edinburgh, near Adelaide, South Australia, where we stayed for two nights.

Somehow or another, my camera was damaged after we left Christmas Island; so, I have no photographs of our return journey. We did, however, get our photographs taken in an Adelaide park (below). John Treherne is back left, Spud is front right and I'm next to him. I believe the other chaps were from The Royal Engineers and The Ordinace Corps.

During the rest of our flight, we spent a night in Darwin, in North Australia, two nights in Singapore, two nights in Ceylon (as Sri Lanka was known in those days), another two nights in Aden, one in El Adem (near Benghazi), one at Malta and, finally, an epic journey ended at Lyneham in the UK.

Almost 50 years later..............

In 1958, there were seven young men who shared a year in the tent shown being erected at the start this journal. A few years ago, I set about trying to trace them and managed to find all but one and we enjoyed a pleasant reunion at The Union Jack Club in London. Since then, we've remained in touch and on the fiftieth anniversary of our return to the UK in 2009, although two of the tank farm chaps couldn't make it, we met again and are shown (above) just before taking a DUKW tour of the capital - which I highly recommend. Other visits we made during the day are shown in this video..........

Around Christmas, 2009, I was contacted by someone who was involved with the RASC Company where we attended our amphibious training course all those years ago in north Devon. Evidently, the site had been sold and they were planning a final reunion because this would be the last opportunity to see the camp before it was turned into a housing estate.

That 'Final Fling' - as it was called - took place in October, 2010, and, along with other former DUKW drivers, I enjoyed four most enjoyable days which combined some extremely well-organised visits to where we did our training together with two informal and one formal dinners at an hotel which had been 'commandeered' for the occasion (below). In addition to the aforementioned visits, a highlight of the weekend was being invited to drive a DUKW in and around the estuary where we had trained all those years ago.

August, 2012.

Although I had been involved with The British Nuclear Test Veterans' Association since its formation in the eighties, by the early nineties - for a variety of reasons - I had become disenchanted with the organisation; so when I heard that a chap called Jim Cooper was exploring the notion of holding less formal gatherings, I attended his first meeting on the south coast. In the event, although the concept appealed to me a great deal and I had actually gone so far as to offer assistance from the point of view of transport (by then I was manager of Guidford Bus Station) my work at that time wasn't really conducive to becoming too involved; so, I didn't attend any more meetings.

In the meantime, over the past twenty years, Jim and his wife, Gloria, have organised several two or three-day 'get-togethers' at various locations around the UK and I met up with them, at their home, earlier this year. As a consequence, I have since managed to persuade three 'members' of my DUKW Drivers group, to join a couple of hundred other veterans of British nuclear tests (not just those on Christmas Island) for a reunion at The Adelphi Hotel in central Liverpool at the end of Ausgust, 2012.

A more detailed account can be found in the Blog section of this web-site, later. However, for the time being here are some photos (below - click to enlarge). Not surprisingly, the Liverpool DUKW tour featured in our itinerary and we're extremely grateful for the complimentary tickets they gave us.

June, 2013.

Sadly, a similar - but rather more serious - sinking occurred again.

Here is a link to an account of the event (including a video).

Monday, 17th. June, 2013.

This evening, having (at quite short notice) been invited to the launch of an art exhibition being held in aid of The British Nuclear Test Veterans' Association, Spud Murphy and I met up in London and made our way to Oxford Street where we spent a pleasant hour-and-a-half viewing the works - whilst being entertained and informed by some of the artists along with officials of the association.

No photos, I'm afraid, but here's an idea of some of what we saw.

Wednesday, 25th. June, 2014.

Recently, I have been introduced to a new - and, at present unofficial (so far as I am aware) section of the BNTVA - which represents children and grandchildren of test veterans. Through their Facebook page, I became aware of what was billed as a Film Premier to be screened within The Palace of Westminster. So, coincidentally almost exactly a year since our previous involvement with the association (see above), Spud Murphy and I met up at Waterloo Station and went to watch the pemiere. A fuller report is available in a Blog.

Recently, I have been introduced to a new - and, at present unofficial (so far as I am aware) section of the BNTVA - which represents children and grandchildren of test veterans. Through their Facebook page, I became aware of what was billed as a Film Premier to be screened within The Palace of Westminster. So, coincidentally almost exactly a year since our previous involvement with the association (see above), Spud Murphy and I met up at Waterloo Station and went to watch the pemiere. A fuller report is available in a Blog.

POSTSCRIPT:

The reason that one person was missing from our reunions has been that my former co-driver, Alan Gott, passed away when he was only in his thirties. Sadly, he is one of far too many who met an untimely demise which, in all probability, was hastened by being subjected to radiation. This journal - which is a completely personal account and any mistakes or inaccuracies are entirely my own - is dedicated to Alan and to those who went with him.